- Home

- Max Kinnings

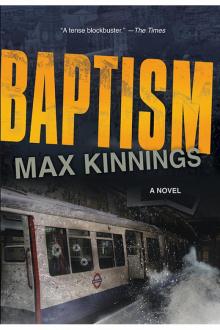

Baptism Page 7

Baptism Read online

Page 7

After an initial desire to pension him off, the force had been good to him, realizing that his ability to listen and intuit potential behavior patterns in hostage takers’ voices was enhanced by his blindness. His stock as a hostage negotiator had certainly risen after he was blinded, although at his most cynical and self-loathing he suspected he was only there to ensure that Scotland Yard achieved its disability quota. That was unfair, although he knew he wasn’t being paranoid when he detected a sense among his colleagues that he was in some way to blame for what had happened to him. During the negotiation, his active listening was not what it should have been. He should have discerned more in the subject’s voice, should have encouraged more dialogue. So, despite his injuries, it was not as a hero that he returned to work and he couldn’t help but feel as though he had been kicked upstairs. His rank sounded fairly grand—detective chief inspector—but most of the time, it was nothing-work. Government liaison. Bullshit. His hostage-negotiation work had developed into something of an obsession but it was an obsession that found little release. There were only so many situations with oil company executives being kidnapped and held for ransom in Nigeria that he could advise on; only so many distraught Fathers 4 Justice to be talked down from on high. To save the lives of innocent people caught up in impossible situations was what he lived for. But as more and more people took the training and became involved in the world of hostage and crisis negotiation, he felt as though he was being squeezed out, marginalized. His special talents, his ability to listen and hear things that others might miss, didn’t seem to count for as much any more. Months could go by and his only involvement in negotiation would be some lecturing and the odd seminar. Perhaps now it was time for a career change? Although job prospects probably weren’t that great for a forty something blind policeman.

Ed clicked up his speed another kilometer per hour on the treadmill and sprinted through the park. The sun shone down on him from a clear blue sky. It felt good. London looked so beautiful today.

8:59 AM

Northern Line Train 037, driver’s cab

George glanced at Pilgrim, who stood and stared into the tunnel, deep in thought. The Line Controller’s voice came through on the intercom once again: “Zero three seven, please confirm your situation.”

“Can you turn him off?” asked Pilgrim.

George was thankful for something to do even if it was something as basic as turning down the volume button on the intercom console.

“That’s better, couldn’t hear myself think. Oh, and you can turn on the light too.”

George flicked off the radio and clicked on the light in the cab. There was no way of reading this guy. He spoke with the generosity of a genial host who wants to make sure that his guest is happy and at ease. But George was very far from at ease. As the seconds ticked by, he felt his claustrophobia intensify.

George knew exactly where it came from. For many claustrophobics, the phobia’s trigger is a traumatic experience relating to a confined space, like being trapped in a lift perhaps. For him, on the other hand, it was reading a short story when he was eleven years old. It was in a book he had borrowed from the school library, a collection of short stories by Edgar Allan Poe. To his young mind the stories seemed very old-fashioned, with a dense, almost impenetrable prose style that had to be deciphered rather than read. He was just about to give up on the book and exchange it for something else when he came across a story called “The Premature Burial.” As he waded into the arcane narrative, he felt an acute discomfort. To be buried alive and to know with every desperate futile scrape at the wooden coffin lid that there was no escape was a concept that haunted him. He couldn’t get it out of his head. The more he tried not to think about it, the more it invaded his mind. And it was from this that his claustrophobia sprang. But, like all phobias, his didn’t follow a pattern. He would be fine in an enclosed space so long as he was moving—hence his ability to drive a tube train—but as soon as he was rendered stationary, the sick feelings, the dry mouth, the sweating, and the breathlessness would descend on him. Only renewed movement or escape from the enclosed space would save him from a panic attack, the strength of which he had no way of gauging, having always managed to avoid prolonged exposure to the requisite stimuli in the past.

When trawling for possible cures for his condition on the Internet, he had found a website that suggested that one of the best ways of counteracting the effects of claustrophobia was nothing more than a type of positive mental thought. It stated that the claustrophobic does not fear the situation itself but the negative consequences of being in that situation. It suggested that a form of self-hypnosis that would infuse the consciousness with comforting “neutral” imagery might be of benefit, along with a repetitious mental refrain that “Everything will be okay.” And when he had tried this method, when held at a particularly long red light in a tunnel, it had worked. To a degree. But this potential cure was not available to George now. At his feet—although he had managed to avoid looking—he knew there was a man with his brains leaking out all over the floor of the cab. He could smell the blood. Everything was most definitely not going to be okay. Not today.

Such was the heat, it was difficult to work out whether he was sweating more than usual, but he could feel his heart pounding in his chest and his mouth felt leathery and dry. Worse still, was the breathlessness. This was what always brought on the worst feelings.

“I’m a claustrophobic.” He said it without thinking. And as he said it, he knew that it was probably the first time that he had ever articulated the truth so bluntly. Maggie knew that his working environment sometimes made him feel uncomfortable but they hadn’t spoken about it for some time because he knew that, under normal circumstances, he could control it. But these were not normal circumstances and something in his subconscious had forced him to speak.

Pilgrim turned to look at him and smiled. “You’re joking.”

“No, I wish I was.”

“You never told me that on the message boards.”

“I never told you a lot of things.”

“Plenty of things you did tell me though, George.”

George winced at the thought of the incontinence of information that Pilgrim had managed to elicit from him. This intense young man had flattered him, massaged his ego, and he had responded. George could remember almost word for word what he had said about how he would do anything for his kids. Pilgrim had intimated that he had had a troubled upbringing. This had made the e-mail exchange become all the more personal. George had enjoyed the role of the comforting older brother. And now this. George had been played.

“So, you’re a tube driver who suffers from claustrophobia?”

“Yeah, I’m fine so long as the train’s moving.” The words came out quickly, breathlessly. “I can cope for a few minutes but anything more and I . . .” And just as suddenly as the words had flowed, they dried up again. The fact was he didn’t know what would happen after a few minutes. He was in unknown territory.

“The thing is we’re not going anywhere.” Pilgrim said it as though he felt genuinely sorry about it.

“Oh God.”

“That’s just the way it is, I’m afraid.”

There was no point trying to act normally. It was impossible. George could feel his heart rate rise; the sweat was pouring off him now and he felt various parts of his lower body, his thighs and his buttocks, succumb to a chill tremble. But it was his breathing that was the biggest problem. There wasn’t enough oxygen to sustain his hungry lungs.

“Deep breaths,” said Pilgrim and, stepping over the body of the trainee driver, he took hold of George’s hands and held them in his. His hands felt rough. The complexion of the palms belonged to a man who was no stranger to manual labor. He stared into George’s eyes, unblinking.

“In,” and he took a deep breath and indicated for George to do likewise. “And out,” and he blew out the air and George tried to copy him. For the first few breaths, George felt no better bu

t, as he surrendered to the slow deliberate rhythm, he felt himself calm down. The fear remained but the panic subsided. There was something about the man’s demeanor, as though he genuinely had George’s best interests at heart. More than that, it felt as though there was some sort of affection in his actions. It gave George hope and this helped calm him even further. This man genuinely wanted to help him, to ensure that he was okay. That he did so because he had a purpose for George was a good sign because if he had a purpose for him then he was not expendable. He would stay alive. And that was all that mattered, that and the fact that his family stayed alive too.

They breathed together for a couple of minutes.

“You’re going to be all right, George. Everything’s going to be fine. I’m not going to do anything horrible to you. Quite the opposite in fact. So don’t despair, don’t be afraid. All you’ve got to do is keep breathing slowly and deliberately and keep happy. This is going to be a big day. Not just for you and me and everybody on this train but for the peoples of the world, who will see it as a sign. Just put your faith in Christ and all will be well.”

George shrugged and exhaled, shaking his head.

“Don’t tell me you don’t believe.”

“Believe in what?”

“Who. Believe in who.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Jesus Christ. Who else?”

“No, I don’t believe. Is that what this is all about, religion?” George turned and looked the man in the eyes. They didn’t look like the eyes of a terrorist. Not that George had ever looked a terrorist in the eyes to know. But there was something kindly and benevolent about the way Pilgrim looked at him. It was as though he felt pity for George—and more so now that he knew that George was a non-believer.

“You must believe in something, George.”

“I believe in nature, evolution, science. I don’t believe in the supernatural.”

The man was nodding at him; the smile had given way to a thoughtful expression.

In the past, George’s lack of belief had provided him with comfort. No cosmic disappointments for him. No self-delusion. There was no God. He knew it; he had always known it. So what was that part of his psyche, that part of his human makeup that now made him reach out to a God in which he did not believe? Where did the compulsion come from? Was it born of desperation? Some sort of psychological clutching-at-straws? Whatever the reason, he couldn’t help himself from pleading for someone, for something, anything, to save him.

“You don’t feel claustrophobic any more, do you?”

The question caught him off guard.

“Not as much, no.”

“You might not believe in God, you might never have believed in him, but hear me when I say that, before today is over, you will.”

George wanted to say, “Never.” He nearly did. But something stopped him. He knew it would sound childish, petulant. There was no point in antagonizing this man.

“The thing is, George,” Pilgrim continued, “we’re going to start a revolution today. Just you wait and see. And when you see the beauty and the truth of what we’re going to do—you and I—then you’ll be a sinner no more and God’s love will fill your heart, now and for always.”

9:16 AM

Northern Line Train 037, sixth carriage

Seated at the end of the carriage, up against the door to the bulkhead separating the passenger area from the rear cab, Maggie Wakeham sat on her hands and stared at the floor. The sick feeling wouldn’t lift. It was like a constantly peaking wave. Maggie felt as though part of her had been amputated with no anesthetic and no concern for her well-being and ultimate survival. Her children were gone, her little ones taken. It was more than an amputation, it was as though the very core of her being had been ripped out and burned in front of her. She hadn’t eaten anything before they came. So there was nothing to throw up, not that she felt she could have retched even if she had wanted to; her teeth were clamped together so tightly, it made her jaw ache.

They were going to Mr. Pieces the night after. It was Ben’s birthday treat. He’d be six. Six years before, she had been in labor. She was in labor for a day and a half. It was horrendous. That’s what she told people when asked to describe the experience. But it had all been worth it. Ben was a beautiful baby boy, and life for her and George was never the same again. Neither was their relationship. It wasn’t necessarily worse—if a marriage can ever be judged on a scale with good at one end and bad at the other—but it was different. More fraught. Less affectionate somehow. She wished that sometimes he’d just take control, just take her in his arms and let passion take over. But maybe he didn’t feel any passion. Maybe it had gone. She hoped not. She still loved him.

They had gone to Mr. Pieces the year before for Ben’s fifth birthday. It was just an ordinary Italian restaurant but it was nice, it was cozy, run by a family. When the waiters—four Italian brothers—wanted to commence the ceremonial singing of “Happy Birthday,” they threw their metal serving trays on the floor, which made a noise like a cartoon thunder clap. Crayons were provided in a little tin bucket in the middle of each table and diners were encouraged to scribble and doodle on the paper tablecloths. The best tablecloth was chosen at the end of each week by the waiters, scraped clean of any surplus food and mounted on the wall.

There was a group of schoolgirls further down the car. They were about seven years old—a little older than Ben—and wore pink dresses and straw hats. Their teachers were doing their best to be reassuring. Seated in their midst was a blind man in a linen suit. A couple of the girls stroked his guide dog. Opposite Maggie was a woman with black hair and black sunglasses. Her casual attire was expensive, fashionable—and all black. Her skin was pale and the only color on her was a slash of red lipstick. She was nervous, kept taking deep breaths and exhaling very precisely through her lips as though it was some sort of breathing exercise. Maggie knew she was a New Yorker. When the train had started out above ground at Morden station, she had spoken into her phone to tell someone that she was running late for a meeting. For a moment, Maggie had considered wrenching the phone from her and telling whoever was on the other end of the line that she was hijacked on a tube train on its way into central London. She didn’t do it of course. All she could think about was her children. She wouldn’t do anything that might expose them to harm.

Next to the slim New Yorker was a man of fifty or so in slacks and a sports jacket. Although contriving to make it look as though he might have been on his way to the golf club, the briefcase and trade magazine spread out on his lap gave away his office destination. Clearly troubled by the long delay in the tunnel, he dabbed at the sweat that trickled down his forehead with a white handkerchief. He looked around at the other people in the carriage. It was as though he was trying to catch someone’s eye. The passengers had remained silent up until now but, as the delay lengthened, people’s nerves got the better of them and the man in the sports jacket was the first to speak.

“How long’s it been?”

The question hung in the intense heat of the carriage. Next to Maggie was a large West Indian man wearing a business suit, his short dreads immaculately disheveled. He looked up at the man in the sports jacket and said, “About fifteen minutes.”

“Oh Jesus,” came the reply. Maggie could tell that his anxiety was clearly being exacerbated by some underlying condition—claustrophobia perhaps. Now that he’d spoken, he needed to speak some more.

“Maybe we should do something.”

“Like what?” said the New Yorker.

“Oh, I don’t fucking know.” His angst made him raise his voice more than he had intended. “I’m sorry.” He looked around nervously as social embarrassment was now added to his anxiety. The New Yorker returned to her breathing exercise and the sports jacket closed his eyes and rested his head back against the window behind him. But he misjudged the distance and the back of his head thumped against the glass. He didn’t acknowledge the pain. When he reopen

ed his eyes a few moments later, he looked at Maggie and she looked away.

The children loved Mr. Pieces. When they’d been there last year on Ben’s fifth birthday, everything had conspired to make it happy and memorable. The children were excited and she had watched their little faces and enjoyed their attempts to order their food from the waiter. Even George, who had become less talkative of late, especially when called upon to shell out for a meal for the four of them that they could ill afford, had opened up and been at his most amusing and charming, playing games with the children and making them laugh. She had watched him and been reminded of the time they went out to dinner together on their first date. That was an Italian restaurant too. They were both nervous and had drunk far too much. Two bottles of wine and a couple of Irish whiskeys each. But George had been a gentleman and put Maggie in a cab back to her flat in West Kensington, where she was living with some old friends from university. He had called the next morning to ask how she was and ask her if she’d like to meet up again in a few days’ time. She was relieved, having spent an agonizing morning, worrying about having drunk too much the night before and whether she had made a fool of herself. Of course she wanted to meet up again. When you know, you know. And after that first night out with George, she knew.

She laughed at his jokes. She liked the way that he didn’t take himself too seriously. He wasn’t one of those pushy types that poison London with their ambition and their avarice. He wanted to do something artistic—make a success of his band or maybe write a book—and she respected him for that.

However much their relationship might have changed in the past few years, she still loved him. She just wished she could love him more, wished that they could both love each other more. George’s problem was that he didn’t much like himself at the moment. He felt guilty for not bringing in enough money. He felt as though life was passing him by and his dreams of artistic expression had come to nothing. It was during the aftermath of their last row, one of those moments when the truth comes tumbling out, that he had told her about his lack of fulfillment and unhappiness. His day job on the tube—while presenting him with plenty of time for dreaming his dreams—also gave him plenty of time to examine what it was that he was doing with his life. She wished he could feel more self-respect. That would make everyone’s life in the Wakeham household that much easier.

Baptism

Baptism