- Home

- Max Kinnings

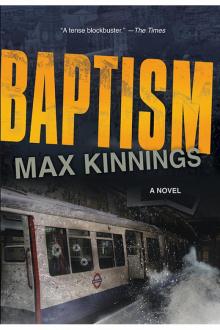

Baptism Page 6

Baptism Read online

Page 6

“Slower . . . slower . . .”

The train moved to walking speed. The man was alert, his turquoise eyes darting around as he looked into the tunnel up ahead. It was as though he was searching for something.

“Okay, now really slow. That’s it, George, that’s lovely. Now . . . stop.”

George stopped the train but he kept the dead man’s handle in the “coast” position out of habit.

George was told to, “Take your hand off the handle now.”

“But it’ll set off the alarm,” said George.

“That’s fine.”

George let go of the handle and they both stared into the tunnel as the motor idled. The line controller came through on the radio: “Zero three seven, is there a problem? You appear to have stopped. Zero three seven? Hello? Is everything all right?”

What would Joe Strummer do?

Pilgrim looked at him and smiled. “Okay, George,” he said, “this is the end of the line. This train terminates here.”

8:56 AM

Northern Line Train 037, rear cab

As soon as the train came to a halt in the tunnel between Leicester Square and Tottenham Court Road stations, Simeon knew that the first part of Tommy Denning’s plan had been concluded successfully. It may have been a week early but everything else was to the letter. It was four minutes to nine by his watch. Tommy had said it would be nine when they reached the target—give or take a few minutes. In the passenger area on the other side of the rear cab door was the train driver’s wife. The three of them—Tommy, Belle, and Simeon—had debated long and hard about whether to take her on the train or not. Belle had said she thought the woman might be a liability, but Tommy had said it was worth having her along in case the driver needed some mental support or further emotional arm-twisting and they could put her on the walkie-talkie and have her talk to him. Simeon had said that he would keep an eye on her, make sure that she didn’t cause any trouble. He had already scared the hell out of her—if she did anything to raise the alarm, her kids would die. As far as the children themselves were concerned, they were all in agreement that they shouldn’t be brought onto the train. It was rough on the train driver’s wife but the trauma and fear engendered by her separation from them would mean that she would be thoroughly compliant. You only had to take one look at her to see that she was going to do whatever it took to see them again. You had to hand it to Tommy, it was a hell of a plan, twisted but brilliant. There was only one flaw in it and that was him, Simeon. If it wasn’t for him, Tommy and Belle might have been able to get away with all this. But he was there to make sure they didn’t. The children would be okay. He would have them out of there soon enough. First he had to let Tommy make his intentions known to the wider world. Once that was done, he could proceed as planned and all the hard work would be over. But despite all that he had had to endure in the past few weeks, there was one good thing to come out of it, and that was getting to meet Belle.

There she was sitting next to him in the rear cab of the train, so cute, so damaged. Despite the extreme, almost insane beliefs that Belle shared with her brother Tommy, Simeon couldn’t help but feel attracted to her. Her lithe, supple body had a vibrant energy to it that was palpable. Even sitting here in the rear cab of the train, having come here to do what they had come here to do, he couldn’t help but find her intensely arousing. This made his emotions all the more conflicted when he considered that, before the day was finished, he would have to kill her.

8:58 AM

Flat 21, Hyde Park Mansions, Pimlico

He clicked up his speed another kilometre per hour. This was the time that he liked most on the treadmill, about fifteen minutes in, when he was all warmed up and the blood was pumping; it felt as though the serotonin was being released. That sense of disappointment that he often felt on waking could only really be lifted by a run. He ran miles every day, here in the corner of his bedroom. It stimulated him on so many levels. It kept him fit, kept his weight down, provided him with “flow”—allowed him to think with more clarity than at any other time of the day. Some mornings were harder than others. It depended on what time he had gone to bed the night before, whether he’d had a glass of wine. Some mornings it just felt right and this morning it felt as good as ever. In a couple of hours, it would be too hot to run. Now, he could really fly.

When he had lived in Muswell Hill back in the old days, he used to run through Alexandra Park. His favorite section was along the front of Alexandra Palace with its views over London. He imagined himself back there now as his sneakers thumped out their mesmeric rhythm. And for a moment, it was as though he had achieved some sort of transcendence and could forget the truth. The sun was shining down on him from the north London sky. To his left was the huge, round stained glass window of Alexandra Palace; to his right London stretching away to the horizon.

Ed reached for the remote control for the stereo and clicked on the radio. It was tuned to a classical station. He used to fool himself that it was soothing. An admission that he needed to be soothed, however, didn’t help and besides, he wasn’t angry any more. Anger had given way to resignation just as all the psychologists said that it would. Acceptance would be next. He hadn’t got there yet. Not by a long way.

The nine o’clock news. “This is Marsha Wilson.” Ed often wondered what Marsha Wilson looked like. He listened to her every morning. He liked her voice; he liked the way she could switch from a serious tone, something she employed when telling you about an earthquake or a pedophile, to sounding smiley and upbeat at the end of the bulletin, when she was reporting a giant squash or someone building their own space rocket in their garage. There was nothing in the news. Nothing interesting. They used to call it the silly season. Everyone was on holiday. The news was canceled for a few weeks. Ed didn’t wish ill on his fellow man but sometimes he yearned for a major incident somewhere, a story in which he could immerse himself. Not today though. All that was on offer today was the weather. It was going to be hot, possibly the hottest day of the year. And next up the first movement from Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 3 in G Major. Not one of his favorites so he brutalized it with the rhythm from his sneakers on the treadmill.

He wasn’t exactly dressed for running—boxer shorts and sneakers—but no one could see him and it was hot. Twenty minutes previously he had thrown some cold water on his face in the bathroom and stepped straight onto the treadmill to warm up with a brisk walk that had developed into a jog and then this, not exactly a sprint but not far off. Running was an effective distraction. Waking up was always a reminder of what had happened just over thirteen and a half years ago. The events of that day might be receding into the past, but they were still as painful as if they had taken place yesterday.

Due to a media blackout, the Hanway Street siege never made the news. But the fact that what happened went unreported did nothing to lessen the torture of its memory.

Conor Joyce was spoken of as something of a legend among Ed Mallory’s Special Branch colleagues. An explosives expert, he was thought to have constructed and deployed a number of devices as part of the IRA bombing campaign. During the late nineties, however, he had found that his services were no longer in demand. What’s more, he had met and fallen in love with a Protestant woman and renounced his fierce Catholicism and accompanying republicanism in order to be with her and subsequently marry her. This fundamental change in his life had meant that when the British secret service came knocking, he turned. MI5 was interested in his knowledge of potential arms caches as they tried to ensure that the IRA complied with the decommissioning terms of the Good Friday Agreement. Yet despite Conor Joyce’s apparent readiness to provide certain limited pieces of information, he was considered slippery and his service handlers were never convinced that his cooperation was not a meticulously constructed false front and that they were the ones being handled rather than the other way around. Nonetheless, some of his intelligence had proved valuable and he was shrewd enough to drip-feed it gradually,

thus prolonging his time on the payroll.

As part of the deal that Joyce struck with the service, he was provided with a flat in Kensal Rise in northwest London complete with a panic alarm, in case his cover was blown and a former colleague from the Provisionals came looking for him.

It was Boxing Day morning when the panic alarm was activated. A Special Branch counterterrorism unit was dispatched to Hanway Street but when they approached the address and tried to enter the building, shots were fired at them and they were forced to withdraw. The entire street was evacuated and sealed off.

It was only Ed’s second official assignment as a hostage negotiator. The first assignment had involved an elderly husband armed with a cricket bat barricading himself and his much younger wife in their home. The man was convinced that his wife was having an affair with a neighbor, but Ed soon realized that he was dealing with someone suffering from mental health problems when it became apparent that the neighbor in question had been dead for a good ten years. After a few minutes of gentle coaxing, the old man put down the cricket bat and the crisis was resolved. Hardly a tough gig, so as soon as he heard the details of the incident in Hanway Street that Boxing Day morning, Ed knew that his training and aptitude would be tested for the first time.

Due to the sensitive nature of the situation, Ed was only one of a larger team made up of Scotland Yard negotiators and MI5 counterterrorist personnel. But he arrived on site first and quickly took up position in the hastily established command center in a flat above a row of shops directly opposite Conor Joyce’s no-longer-safe safe house. It was apparent that Joyce’s cover had indeed been blown and he was being held hostage by an IRA hit man who had come to kill him.

Whether or not the hit man had succumbed to an attack of conscience when he found the target of his hit with a heavily pregnant wife was never established, but the subject—as he had now become in the language of crisis intervention—was using his hostages as bargaining collateral. If he was granted safe passage with them, he would allow them to go free once he was at his chosen destination. If not, they would both die. He had a hand grenade from which he had removed the pin and he made it known that if a marksman were to try and take him out then everyone would wind up dead.

There was no way the British government would allow the escape of a known IRA hit man from the scene of a hostage-taking, so Ed settled in for a long negotiation. The subject, however, wanted to play things differently. He was impatient to talk. Ed was nervous but also excited. He would play it by the book, maintain an ongoing dialogue, calm the subject, establish trust, and gather information through active listening, all skills he had acquired through his extensive training.

But the subject was like no other hostage taker that Ed had ever come across in the case studies. He was a hardened Provo who would stop at nothing for what he believed in, and what he believed in, caged in that small flat in northwest London, was his need to escape.

“My name is Ed Mallory, I’m a negotiator and I would like to help.” Name, role, and intention—a standard opening gambit once telephone contact has been established with a subject.

The heavily Irish-accented voice on the other end of the line came through loud and clear.

“Fuck off, you stuck-up cocksucker, don’t give me any of your psychology shit.”

And from that moment on Ed knew it would be a tough negotiation, one that would require all his guile and ingenuity to resolve. It was unlikely this subject would respond to the standard crisis-intervention techniques. The man was working from a totally different set of moral values to those subjects Ed had studied up until then. But Ed was young—not yet thirty—and he was confident that he could get through to him. He was ambitious and he wanted to show his colleagues and superiors that he had what it took.

Ed tried to find out the subject’s name but got nothing but obscenities. He tried to calm the subject down by telling him that he felt uncomfortable with his use of profanity. Bollocks, fuck you—more profanity. Whatever he said, he could not get through to him. The guy was completely unreadable and his behavior followed no accepted pattern. He went from anger and frustration to a calm psychological detachment with no apparent transition. Ed had never come across anything like it. He was one of those rare subjects that an FBI crisis-intervention trainer had told him and his fellow students about in a seminar once: someone completely impervious to all negotiation methods. Freud had said of the Irish, “This is one race of people for whom psychoanalysis is of no use whatsoever.” Maybe the same applied to them in hostage negotiation.

The subject issued a demand and a deadline. Unless he had a call from Ed by four o’clock to say there was a car to take him and his hostages to a light aircraft, which would deliver them to an unspecified location in the Irish Republic, he would let off the hand grenade.

Ed knew all about deadlines. They held a central place within the study of hostage negotiation. He also knew that there was no way the subject was going to be allowed to go free. Ed was sure the subject knew it too. So he decided it was a choice between two distinct paths of conduct: he could either stall him, tell him that four o’clock was unrealistic and he would need more time, or he could try and gain the subject’s respect by acknowledging that his demand was never going to be met and try to resolve the situation in a spirit of brutal honesty. He opted for the latter, told the subject straight. There was no way the authorities would let him go free.

“You’ve got until four,” came back the reply and the line went dead. Ed told his superiors and the other members of the team who were now in situ that he thought the best thing to do would be to call back the subject a little before four to negotiate a new deadline just as the existing deadline was expiring. An effective tactic that he had learned in his training. Everyone agreed.

Ed was nervous as he picked up the receiver at five to four and dialed the number. He looked across to the first-floor window of Conor Joyce’s flat only thirty feet away. The narrow street was deserted. All the properties were empty, apart from the snipers staring through telescopic sights at the same single window as Ed.

He could just make out the sound of the telephone ringing in the flat across the street. The call was answered and Ed started talking.

“What you’re asking for is proving very difficult. I’m doing my best but you’re going to have to give me more time.” Ed had prepared himself for objections but the response from the subject was surprising: “Okay, mate, that’s fine. At least we know where we stand.” He sounded calm, almost cheerful. For a moment Ed felt a surge of confidence before he realized he was being reassured by the subject for no tangible reason, a characteristic often displayed by potential suicides when they have finally decided to kill themselves. Ed knew he had to act fast, had to establish a new line of negotiation. But he didn’t get the chance. It was discovered subsequently that the subject had spent fifteen years in the Maze Prison. He wasn’t going back. The sound of the explosion relayed into Ed’s ear through the telephone headset gave him tinnitus for two weeks.

It wasn’t his ears, however, that were the problem. He hadn’t even considered the potential force of the blast. All that separated him from the exploding hand grenade were two panes of glass and one of those panes was only inches from his face. His face would be scarred for life, but as with his ears, that was a small price to pay compared to the blast’s primary damage: glass fragments were embedded in the orbital tissue of both eyes. His left eye had a prolapsed iris; both eyes suffered multiple perforations of the cornea. The facial lacerations healed. People told him that the scarring wasn’t too bad, which meant that it probably was. He would never know. According to the doctors who ran the tests, his left eye retained about thirty percent light sensitivity. He could see shadows but little else. The trauma his right eye suffered was such that for a couple of days after the injury, it was felt that it would have to undergo enucleation—complete removal. As it turned out, it ended up staying where it was, although it was totally redundant.

<

br /> The grenade explosion killed the subject and Conor Joyce’s wife and unborn child. Conor Joyce survived the blast but with multiple injuries. He was conscious—in great pain but still lucid—when they brought him out of the building.

Conor Joyce kept shouting, “You fucking let her die!” over and over again as he was loaded into the ambulance next to the one in which the paramedics worked on Ed. And in a way, he was right. Maybe Ed had let her die. For a long time afterward he blamed himself for what happened. Joyce’s wife was the first person he would ever lose during a negotiation. There were others after her, both hostages and subjects. During his career, he had been involved in over forty-five crisis situations throughout the world, from the United States to the Middle East. Forty-three of those had been as a blind man. By the law of averages, he was bound to lose a few and he had learned to accept that sometimes, ultimately, you cannot take responsibility for someone else’s behavior. People do what they want to do and even if you are armed with an acutely intuitive understanding of how individuals react to crises, sometimes you are unable to stop them.

For the most part, when subjects and hostages had died on his watch, Ed had dealt with it in his own way. Even when he had spent hours and sometimes even days in intense negotiation and really felt that he was getting somewhere with a subject and they had gone on to kill themselves or others, even then he had been able to assimilate it. But not so Conor Joyce’s wife, and it was to her that his thoughts always turned, her death coinciding with the exact moment when he lost his sight. She was the only one he felt he had let down, just as he had let himself down in the process. He had been too cocky and self-assured, too keen to impress his superiors. If he had intervened with the subject earlier, if he had stalled more effectively, if he had encouraged the subject to open up more. If if if. Conor Joyce’s wife haunted him every day of his life. It was as though he had been imprisoned on the day she died. Over and over, he was told he would finally come to terms with his sightless existence. Thirteen years now and he was nowhere nearer to accepting it. Maybe if he could then he could get on with his life.

Baptism

Baptism