- Home

- Max Kinnings

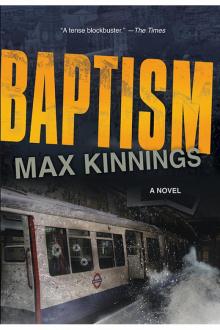

Baptism Page 13

Baptism Read online

Page 13

In the second carriage, a man in his mid-thirties with no history of heart problems was complaining of shooting pains in his chest and was being made comfortable on the floor of the carriage by a porter from Guy’s Hospital.

Empty water bottles and lunchboxes were used to urinate in. People stood in the corners of carriages and shielded one another. Two adults and four children on the train had by now soiled themselves.

In the first carriage a Greek woman who ran a restaurant in Brighton and was visiting London to meet an old friend from school decided that she wanted to speak to the driver. It was at least fifteen minutes since his last announcement that they would be evacuated from the train imminently and she wanted to find out what was going on. She banged on the door to the front cab.

“Driver!” she shouted. “Open the door! Driver!”

George Wakeham was heartened by the sounds of potential insurrection from the other side of the bulkhead. Denning told him to make another announcement.

“This time, George, sound a bit more convincing, will you? Sound heartfelt. Tell them you’re doing all that you can. Don’t worry, they’ll believe you. They still have no reason not to. And get the woman on the other side of the door to shut her mouth while you’re at it.”

George picked up the handset.

“This is George, the driver, again. I’m really sorry about this extended delay. I’ve spoken to the controller and I’ve been assured that we will have you out of here soon.”

If he were a hero, he would tell them the truth; he would quickly tell them that the train had been hijacked and they should try and escape. Some of them would manage it. Their sheer weight of numbers would make it a mathematical certainty. But George was not a hero, not in his own mind. All he wanted was to see his wife and children again and he would do nothing to jeopardize that.

“I’m really, really sorry about this, everyone, I’ve been assured that we’re being kept here for safety reasons. I realize that it’s incredibly hot and stuffy but I’m being advised that we have to stay put. So please just sit tight and I’ll keep you posted. Oh and to the lady who keeps banging on the door here and shouting: can you please stop because it’s giving me a headache?”

“I like it,” said Denning as George replaced the handset. “You’re getting better at this.” Denning’s amused little smile, the wry curl of his top lip, was really beginning to bug George. He had never thought of himself as a violent man but how he longed to banish Denning’s smile by driving his fist into it.

“Can I ask you a question?” said George.

“Looks like you just did.”

“Why are you drawing this out? Why not just do whatever it is that you’ve come here to do?”

At least the question put a stop to the smile.

“Don’t you know anything about theater? Performers don’t just walk on stage as soon as the audience arrives. That’s not how it works. You have to build up the audience’s expectation; you have to let them get high on the anticipation of your performance. You have to make them wait. It’s all about show business. Before Adolf Hitler arrived at his rallies, he kept the crowds waiting and then finally he would arrive by helicopter. He literally came down from the sky. That’s powerful symbolism. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a fan or anything, but the man knew a thing or two about how to make an entrance. And, anyway, I’m waiting for the media to ‘set up’ as the expression goes. I don’t want anybody to miss anything and it’s barely even breakfast time in New York.”

George felt like asking him, if Hitler’s symbolism was that he came from the sky, what was Denning’s? Emerging from underground—was his symbolism that he came from the sewers?

It seemed to George as though Denning was becoming more confident as time went by, as though he was feeding off the power that the situation had given him and drawing strength from it.

“Now I want you to get on the line to that Ed Mallory bloke and tell him that you’ve got the first of your demands.”

“My demands?”

“You know what I mean.”

“And what is my first demand?”

“You can tell him that I want a wireless router installed in the mouth of the tunnel at Leicester Square station so that the entire train will have access to the Internet. There must be no passwords required, nothing. It must be Internet for all. I want everyone on this train connected to their loved ones. I’ll give them until eleven-thirty to put it in place and then I’ll start killing the passengers, one for every minute I’m kept waiting over the deadline, in the accepted Hollywood manner.”

10:41 AM

Network Control center, St. James’s

“George, you need to ask the person you’re with to speak to me directly otherwise we’re not going to be able to sort this out.”

“That’s not possible. You need to put the router in place by exactly eleven-thirty, at the latest, otherwise the passengers start to die.”

“I can’t promise that I can do that. I have to speak to the powers that be. I’m not sure if it’s even feasible, technically speaking.”

“It is and it needs to be open access. Any attempt to limit the signal in any way will be taken as a failure to comply and the passengers will start to die at a rate of one a minute.”

“George.” Ed lowered his voice to make it sound as conspiratorial as possible, knowing full well that whoever was with him would be listening in. “You need to tell the person you’re with that it’s extremely unlikely that I’m going to be able to fulfill their request. Getting a makeshift Wi-Fi signal along the tunnel to the train is going to be difficult. If I can speak to this person directly then it’s more likely that I can find out exactly what it is that they want and I can set about trying to do what I can to help.”

It was all bluster, anything to get the subject on the line. Ed knew that his confidence would be boosted immeasurably if he could hear a voice, hear the words and their delivery. Without them, there was no way that he could build up a profile, no way to deconstruct the perpetrator’s personality and start working on him.

“You’ve got until eleven-thirty and then someone dies.”

“George?”

It was too late. Ed was talking to a dead line. He took off the headset and put it down on the desk. He rubbed his hand across his face, his fingers sliding across the ridges of scar tissue.

“Ed, this is Laura Massey,” said Calvert. “She’s going to be the negotiating cell’s coordinator.”

Ed was pleased it was Laura. They had worked together once before on a siege in the East End. Four days they had spent together, locked up with the rest of the negotiating team in a council high-rise, trying to talk down a crack-addled father of seven who had taken his wife hostage after finding out that she had been having an affair with his brother for the past five years. It was a grueling negotiation but he had found Laura to be fiercely professional and also human. In addition to her skills at running a successful negotiating command center, she was also an excellent negotiator in her own right.

Ed held out his hand and Laura shook it. Her hand felt soft and dry. She didn’t wear perfume; her aroma came from a combination of deodorant and moisturizer. Ed liked it.

“Hi, Laura. Are we going for a standard cell?”

“Yes, Ed, you’re the number one, Calvert and White here are numbers two and three respectively.”

“I understand we’re staying here for the time being,” said Ed.

“That’s right, we can set up the console and plug it straight into the London Underground system so we can have direct access to the radio in the driver’s cab on the train. We’ll look at moving to the command center later on if we need to.”

“Presumably Serina Boise is incident commander.”

“That’s right. She wanted me to reiterate to you that MI5 must be kept in the loop on everything.”

“Yeah, right.” Ed didn’t care if his displeasure at this was apparent to Mark Hooper, who was standing nearby, or to anyone

for that matter. There was no point wasting time thinking about it but conversely there was no getting away from the fact that the constant affirmation of MI5’s involvement was just plain odd.

“Any news on the Wi-Fi?” asked Ed.

“They’ll have to employ some heavy-duty hardware to get the signal far enough into the tunnel to reach the train. But it should be possible.”

“Good,” said Ed. “We’ll turn it on just after the deadline has passed. I realize we’ve got hundreds of people down there in extreme conditions but we must still play for time. The normal rules apply. We slow this thing down. There’s no rush. We’ve got all the time in the world.”

“And what happens when they’ve got Internet access down there?” asked Hooper.

“Well, unless we can restrict it in some way, then they go live to the world. With just a shop-bought laptop, they can broadcast sound and vision anywhere they like. They’ve got their very own reality TV program.”

“That can’t be a good thing,” said Hooper. He said it in such a way that it felt to Ed as though he was taking this situation personally, as though it made him resentful in some way.

“What’s the alternative?” asked Ed.

“Well, we have no control over the Internet. Signals can be made; messages sent to accomplices.”

“It’s a risk we’re going to have to take for the time being. It could even work in our favor. They’ll have a communication link but so will we. We should find out the identity of as many passengers as possible. You never know, we might find there is a person—or persons—who has the knowledge and expertise to launch a counterattack from within the train. Failing that, we should still be able to harvest valuable intelligence. The passengers can act as our eyes and ears. Just as much as the hijackers want to use the Internet to broadcast their message, we can use it against them. We need to have GCHQ analyzing all communications, every single word that is spoken in a conversation, every e-mail. We must be constantly updated on everything going into and out of that train.”

“I’m still not sure.” Hooper again.

“We have no alternative,” said Ed. “If what we are being told is true, they’ve already killed two men. And anyway, the Wi-Fi also provides us with bargaining collateral. We give them that then ask for something in return. What do people think?”

“Children out?” Hooper suggested.

“We’ll try if we get the chance but I have a feeling we won’t succeed.”

“Why not?” asked White.

“If they want to freak us out, which is what I think is going on here, then keeping the kids in there is going to do just that.”

Over the years, Ed had tried to condition himself to think that the number of hostages in any given situation was immaterial. But it was difficult. A big number was always scary. Like the RAF Brize Norton hijack of 2003 in which a soldier on his way to Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom kept sixty-four fellow troops and crew hostage for a day and a half, threatening to blow himself and the plane up with a couple of hand grenades. It never made the news. The authorities wanted it that way but it didn’t make it any less stressful. When Ed had managed to talk down the squaddie—a nineteen-year-old with mental health problems—it was an achievement for which he felt some pride. Although that pride had soon turned to frustration when the gold commander on the incident had suggested that it was his blindness that had provided him with his abilities, as though anyone who was blind would be able to resolve an extremely complex hostage situation.

He’d always been good at listening to people. It was instinctive. Even as a young child, he seemed to have a natural understanding of people’s moods and feelings. He had an aunt, his father’s sister, and it was clear to Ed that she was troubled. Others didn’t seem to see it. He didn’t mention anything to his parents. How could he? He was a child. But his suspicions were confirmed when she had a nervous breakdown and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital from which she never returned to normal society. But whenever he visited her—and sadly it wasn’t often—the nurses would tell him that it was in his company that she was at her most calm and contented. It was this natural ability to communicate with people and make them feel comfortable that had proved a crucial asset in his professional life. And it wasn’t just with hostages on the other end of a phone line. It didn’t matter who it was: he had the ability to put people at their ease. It was as though he didn’t have an agenda. And maybe that was because he didn’t, not at the moment that he was speaking to someone. He could focus on another person’s point of view; he could empathize. Other hostage negotiators he had come across—most of them—never allowed the purpose of the hostage negotiation to slip into the background. It was always there, like the elephant in the room. But Ed could create a relationship with a subject and even if only momentarily, the subject could forget about their often desperate, life-or-death situation. With one subject in a crisis situation in Nigeria, he had discussed Manchester United’s UEFA Cup chances. “Keeping the channels open,” he had heard it called by psychologists. This skill, whatever it might be called, could not be taught. Ed had it—had always had it—and it helped.

But everything that had gone before in his career now paled into insignificance. He was faced with a gang of terrorists of an indeterminate number with hundreds of hostages and no apparent motive other than a desire to achieve communication with the outside world. It was this desire for communication, however, that gave Ed some hope. If they wanted to harm the passengers, they would have done so already. It appeared that what they really wanted was media exposure and once they had that, it was possible they would let the passengers go. He could exert control over them by threatening to cut off the communication. The apparent enormity of the hijack and the potential loss of life might just be a smokescreen for something else; and if he allowed his optimism to have free rein then maybe the two CO19 guys were not dead either. Perhaps they were being held hostage and their demise being reported only as a means to give the impression that the hijack was a deadly serious venture. The thought that this might just be some sort of crazy publicity stunt allowed Ed comfort. Misguided theatrics he could deal with. It was terrorism that made him nervous.

11:02 AM

Northern Line Train 037, sixth carriage

Despite the intense heat, Hugh still had his sports jacket on. Maggie couldn’t decide whether she wanted him to suffer another panic attack or not. Part of her wanted something—anything—to happen, a situation to develop that would force the truth on her fellow hostages, make them realize that they were hostages. Another part of her, however, wanted nothing, least of all some loose cannon jeopardising whatever chance she still had of seeing her family again.

Why them? The question came to her once more. Of all the train drivers who worked for London Underground, what twisted confluence in the random streams of chance had led these people to their door?

Whatever thoughts she could muster that were not concerned with Sophie and Ben, and where they might be and what might be happening to them, were a welcome relief from the crushing despair. When they had told her that she was to be separated from the children, she had tried to scream and shout out to passersby—they were in the street at the time—but the Asian man had put his hand over her mouth and told her that if she continued to shout he would personally kill the children himself. She hadn’t seen the other man—the white man with the shaven head—or Sophie or Ben after that. She fired questions at the man and woman who accompanied her into the tube station but all she was told was that the more questions she asked and the more protestations that she came out with the worse it would be for her.

“If you don’t shut up, we’ll kill them.” The woman had said it a couple of times. By the time they were on the train and the two hijackers had gone into the rear cab, Maggie knew she had to keep quiet, play dead, until such time as she could work out if there was anything she could do.

Hugh was on his feet again. He looked across at Adam opposite, as though willing

him to calm him down like he had done the previous time.

“There are people in there having sex.” Hugh gestured at the door to the rear cab. “They’re in there screwing. Can’t you hear them?”

Maggie had heard them; Adam must have heard them too. They weren’t loud, but it was unmistakable, the meaty rhythm, the breathing and the muted gasps.

Adam stood up. “It’s okay, mate. It’s all right.” He placed his hand on Hugh’s shoulder but before his attempts to soothe could take effect, Hugh had broken free of his grasp and taken a run at the door to the rear cab, charging at it with his briefcase held up in front of him like a battering ram. The case crashed against the rear door and as it did so, he started to shout, “I can hear you. Stop it! Open the fucking door!”

His leg was pressed against Maggie’s and she could feel him trembling through his trousers. Adam was close behind him: “It’s all right, mate, calm down.” But Hugh managed to take another swing at the door with his briefcase before Adam could restrain him.

11:07 AM

Northern Line Train 037, rear cab

On the other side of the door, Simeon and Belle heard the commotion but as they were both reaching orgasm at that moment, it was all they could do to refrain from crying out. Sweat came off them as though they were in a sauna. Belle relished the feeling of their bodily juices comingling. It felt as though they were both made of liquid. It might have been the forbidden nature of the situation, it might have been because it was today of all days but Belle was certain that she had never experienced an orgasm as intense as that before. She leaned up and pressed her lips against Simeon’s, her tongue writhing against his. She wanted to savor this feeling. He placed his hands around her neck. His thumbs dug into the flesh; she loved his strength. He was still hard and he pushed himself into her one final time before their hungry grinding came to an end.

Baptism

Baptism